Software development for research projects

Last week, at the OVI lab’s weekly meeting, I presented my approach to writing software artifacts for research projects. The slides are as follows:

In this blog post, I am going to elaborate and expand on the presentation (mostly for my own reference).

Pretty much always the software artifacts in research projects are not something that are carefully planned and thought out. It usually starts with something like “This is a cool idea, let’s quickly cook something up and see if it has any substance”. If it does pan out, then do a little bit more to see if it is worth further exploring. Along the way, a whole array of problems show up and you add patches to solve them. More often than not, you end have having to completely pivot, for a million different reasons, which makes the code base look a lot nicer. When you reach a point where it can be used to start running experiments and collecting data, you add a few more things to be able to do that. What ends up happening is the interesting ideas/tools get buried inside all the explorations, configurations, checks and balances you added along the way. If you want to extract the useful components, ideas or tools, either to distribute them as packages others could use or even for you to use in projects down the line, you end up having to do a MOJOR refactor, which is never ever fun.

What I am going to talk about in this article is how I approach any software development for research projects so that the artifacts are more maintainable while also adding as little overhead to the research process as possible.

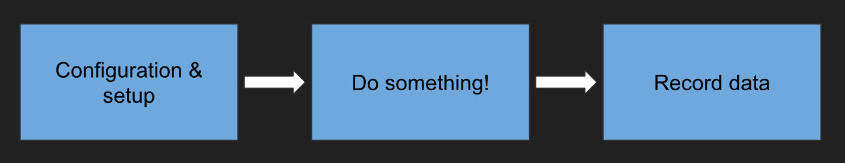

As described above most software components in research projects do the following: Given a set of configurations/parameters, do something and then collect data. For example, If you are doing a machine learning project, you provide parameters that would configure, train and test the models. You may have multiple different configurations, implementations, etc. Then you collect and compare the results. Another example: You are running a user study comparing two different interaction techniques. Based on some criteria, for each participant you administer conditions where they do something with the interaction techniques then you collect data from it and analyze it. From what I have seen so far, this pattern applies to the vast majority of the research projects.

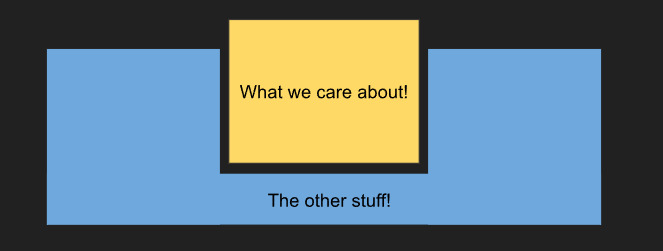

For any given research project, it is the “doing something” part that is of interest. In fact, numerous tools out there do the “configure & setup” and “record data”. Given my background in ML and HCI, I have worked with MLOps tools like mlflow (which can be used for user studies as well, that’s probably another article) and UXF in Unity. My colleagues who work on brain-computer interfaces use tools like OpenViBE. Most of these tools combine both the “configure & setup” and “record data” pieces. So I am going to combine them into one component - the “other stuff”. There is one “gotcha” with these tools that I’ll come back to later in the article.

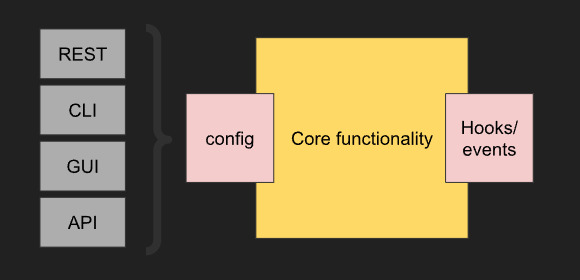

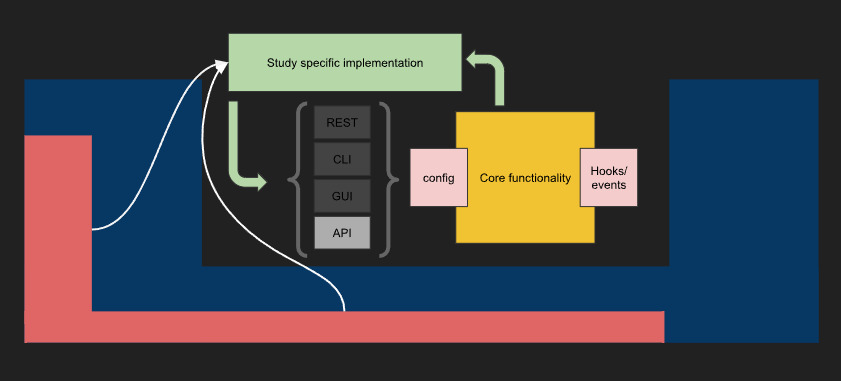

When I set up any project to start exploring an idea, I set it up such that it would/could be a package. There is something to be said about experimenting on a throwaway project and starting over once you get a hang of it, but that’s another conversation altogether. Whatever functionality I am implementing, I approach it like developing a tool. The core functionality is written as function(s)/class(s). This core would take in parameters or configurations and have hooks & events in places I might want to get data from. Depending on what it is I also would wrap it and provide other interfaces to it, like a REST API or a CLI. These wrappers are thin layers you can set up with very little effort.

What this allows me to do is, import it anywhere I want and use it. It can be in an experiment or a different project which uses this as a feature. Also, when I want to demo/test it, I can spin it up without having to deal with all the overhead that comes with the experiment-related code.

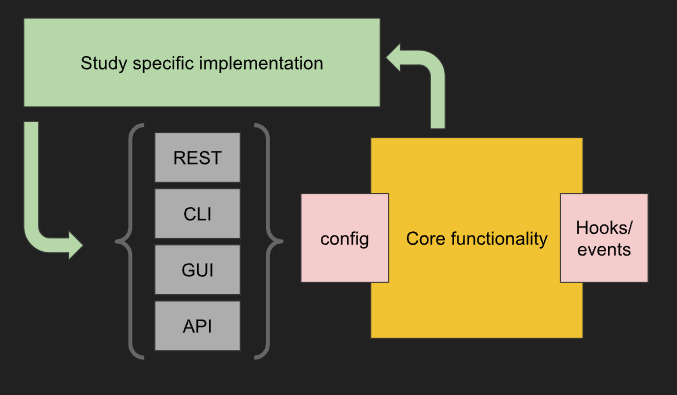

Coming back to the science, when running experiments, I would have a simple setup that configures the “core functionality” using one of the given interfaces, and also add hooks anywhere I need to record data.

This most likely would be wrapped in the whichever “other stuff” I am using.

I mentioned a “gotcha” with the “other stuff”: Sometimes, you want to be able to manage the flow of the study without having to re-run the whole thing. With ML projects you could ctrl+c and use the last checkpoint (or something like that) to test. But this is not a good option when you are running user studies. You want the study to proceed with minimal input to avoid human errors. But you also want to have control of the flow in the off-chance something goes wrong. I’ve seen different people use different solutions to that. I had written a Python package for that - experiment-server (https://github.com/ahmed-shariff/experiment_server) and an associated UXF extension to use it with Unity projects (https://github.com/ovi-lab/UXF-extensions). That would be the red part on the “other stuff” in the figure below. The study implementation would query the experiment-server to get the configuration information to load before each block. This lets the study progress without input, but when necessary, I can step in and control the flow if needed.

Most of what I am talking about here will not be much of a surprise for anyone with a software engineering background. But once you start to dig in, even with the SE experience, you tend to miss stuff.

As of writing this article, this is how I am approaching projects. As with anything else, it’s always evolving.